Supply Chain Resilience Initiative – Need, Challenges, Way Ahead

With the coronavirus pandemic and the US-China trade tensions threatening the global supply chain, Japan had called for a tripartite Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI), with India and Australia as other two partners. The three countries have decided to launch the initiative to build resilient supply chains in the Indo-Pacific region later this year.

This topic of “Supply Chain Resilience Initiative – Need, Challenges, Way Ahead” is important from the perspective of the UPSC IAS Examination, which falls under General Studies Portion.

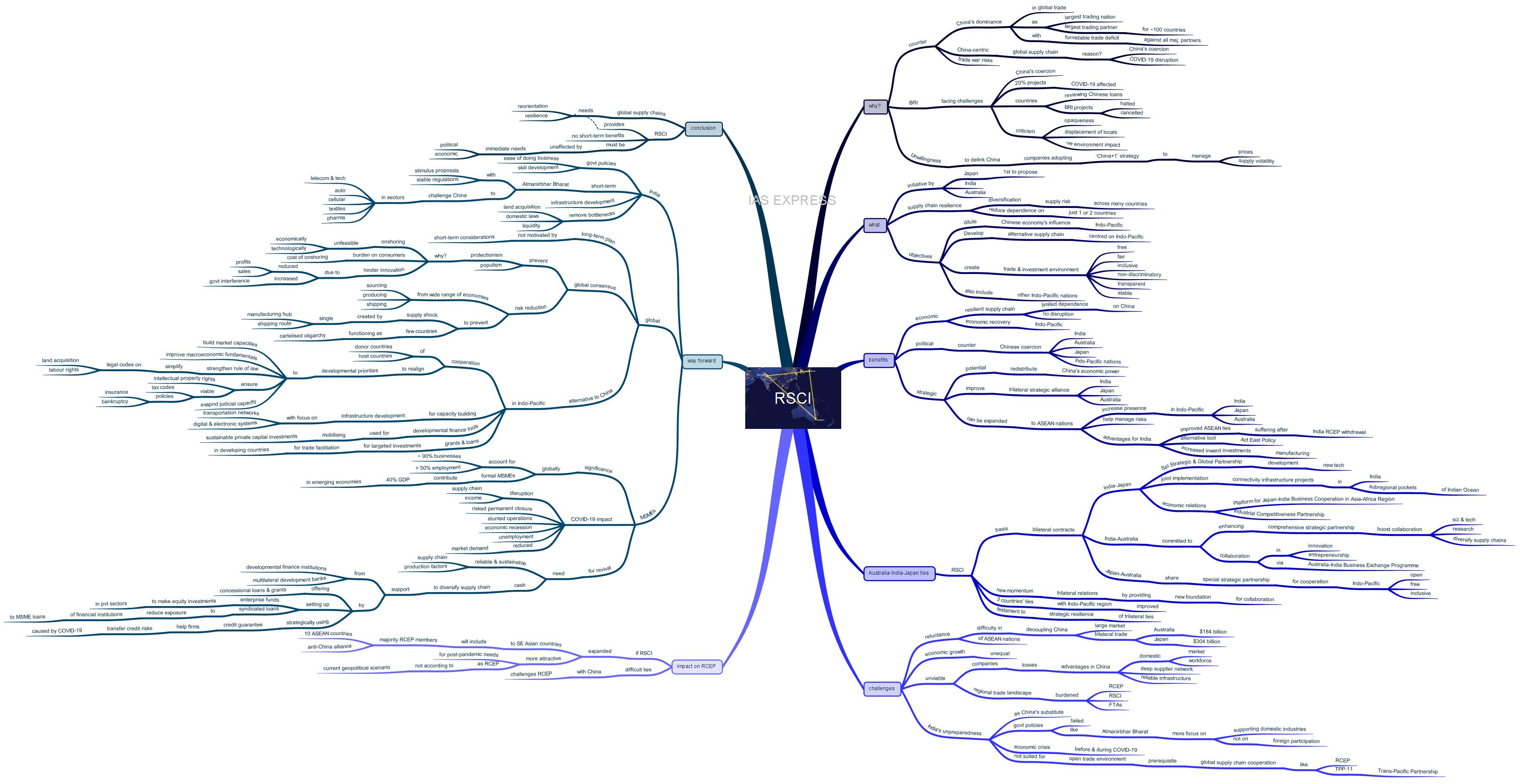

Why is a resilient supply chain necessary?

Chinese dominance:

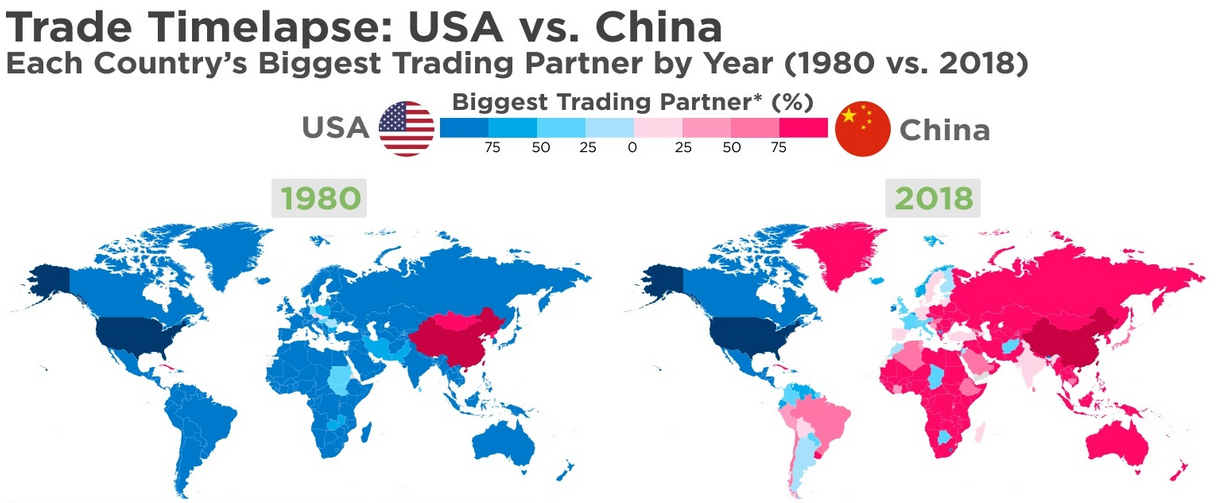

- China’s dominance over global trade has been a major concern for over a decade now.

- It has become the world’s largest trading nation and the largest trading partner for over 100 countries.

- It has also built a formidable trade deficit against all its major partners.

The vulnerability of the Chinese market:

- The SARS-CoV-2 started ravaging China in late 2019, forcing China to shut down most of its key manufacturing hubs in Hubei province.

- This has sent shock waves throughout the global supply chain, affecting production operations all across the world.

- Production disruption in China affected various industries across the world, including automotive, pharmaceuticals, electronics and consumer goods, leading to several countries re-evaluating their supply chains.

- The coronavirus outbreak has been a wake-up call for the major powers to address the issue of their supply chain becoming China-centric.

- Beijing is currently making use of its economic prowess to threaten an import ban on countries that are blaming it for the pandemic outbreak.

- The coercive strategy used by Beijing during this pandemic deviates from its earlier tactics of incentivising trade and investments to cultivate internal instability via the BRI.

- This deviation can be attributed to the current challenges faced by the initiative.

- On June 2020, the Chinese government announced that around 20% of the BRI projects had been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Countries like Egypt and Bangladesh have halted or cancelled some of these projects.

- Many countries are reviewing Chinese loans due to the fears of debt-trap diplomacy.

- These projects are also being criticised for their lack of transparency, displacement of local communities, adverse environmental impacts and many other issues.

- The opportunity provided by the pandemic and the growing unpopularity of Beijing in the international arena is being made use of by the countries to diversify their supply chains

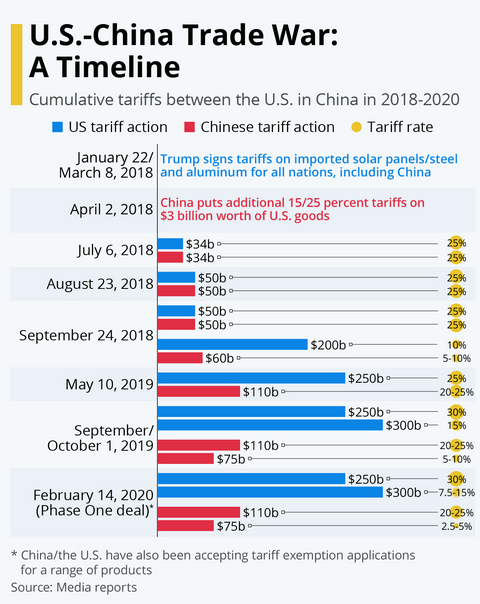

- The blame game over the COVID-19 pandemic has reignited the US-Chins diplomatic tensions.

- If these tensions would continue to escalate further, the dispute could morph into a damaging conflict that threatens the global recovery from the pandemic.

- Furthermore, they would also significantly deescalate the global technological progress, with the US restricting Chinese tech firms from manufacturing and obtaining necessary supportive technology for the development of Artificial Intelligence and 5G technology.

- It should also be noted that, with the US becoming the worst affected by the COVID-19 and its Presidential Elections nearing, it has become highly unreliable in countering China’s growing economic dominance.

Unwillingness to delink China:

- Most companies are not delinking businesses with China.

- They are, however, mulling the adoption of a ‘China+1’ strategy to diversify supply chain so as to manage their prices and supply volatilities.

- This is to reduce the risk of becoming a hostage to China’s whims.

What is Supply Chain Resilience Initiative?

- On 1st September 2020, India, Japan and Australia committed to cooperate towards a new Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) in the Indo-Pacific, which is to be launched later this year under their trilateral partnership.

- In international trade, supply chain resilience is an approach that helps a country to ensure that it has diversified its supply risk across numerous supplying nations instead of being dependent on just one or a few countries like China.

- The objectives of this initiative are:

- To dilute the Chinese economy’s influence in the region

- Develop an alternative supply chain network centred on the Indo-Pacific.

- Create a free, fair, inclusive, non-discriminatory, transparent, predictable and stable trade and investment environment

- Japan, the world’s third-largest economy, was the first to propose this initiative.

- It, along with India and Australia, has called on the other nations in the Indo-Pacific, which share similar views, to participate in the initiative.

- The ultimate goal is to stand up to China and significantly reduce its economic influence so as to limit its interference and coercive diplomatic tactics.

What are the benefits of SCRI?

Economic gains:

- The SCRI would enable the building of a resilient supply chain that is either independent or barely dependent on China.

- This would prevent supply chain disruption as seen during the initial stages of the pandemic when the ceasing of production from China had caused cracks in several supply chains across the worlds.

Political gains:

- SCRI would also counter China’s political aggression with many countries across the world.

- India, Japan and Australia are among those countries that are currently finding it difficult to manage their ties with China.

- Tensions with Beijing are a common trait across most of the Indo-Pacific.

- With the US-China worsening, the Indo-Pacific has become a common ground for rallying against China.

Strategic gains:

- Under this trilateral framework of cooperation, the SCRI has the potential to boost economic recovery in the region and redistribute China’s economic power.

- This could pave way for a better trilateral strategic alliance between India, Japan and Australia, which are the members of the QUAD along with the US.

- If successful, the SCRI could be expanded to the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

- If this happens, India, Japan and Australia can increase their presence in the Indo-Pacific and counter China’s dominance in the region.

- The ASEAN nations are currently restraining their choices, as China is the only viable partner in many cases.

- In reducing their dependence on China through SCRI, they can better manage their risks.

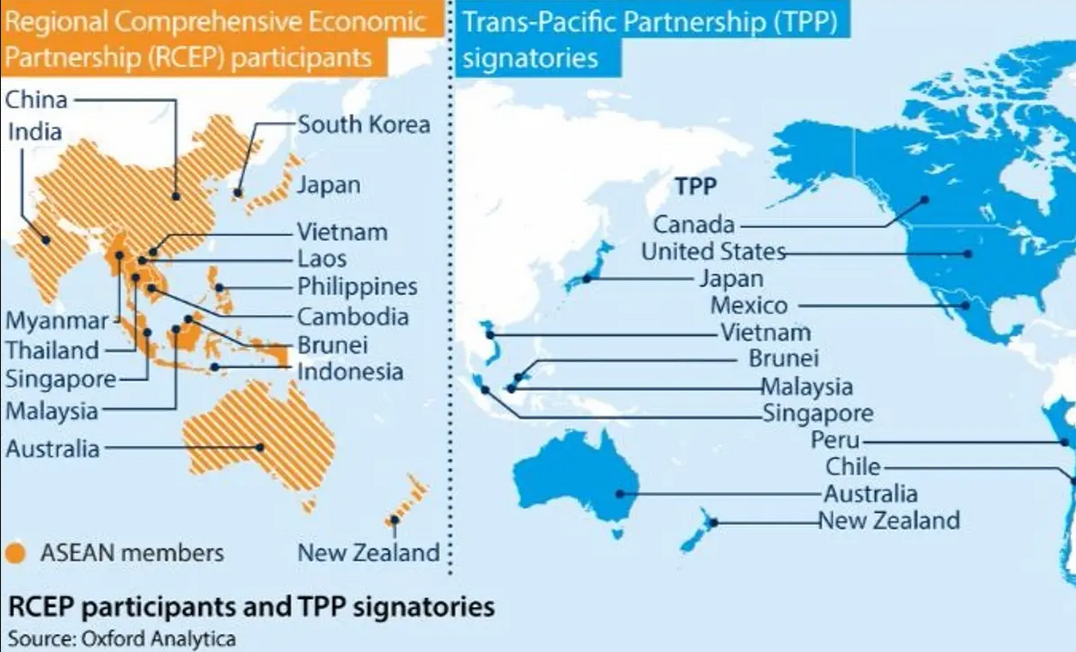

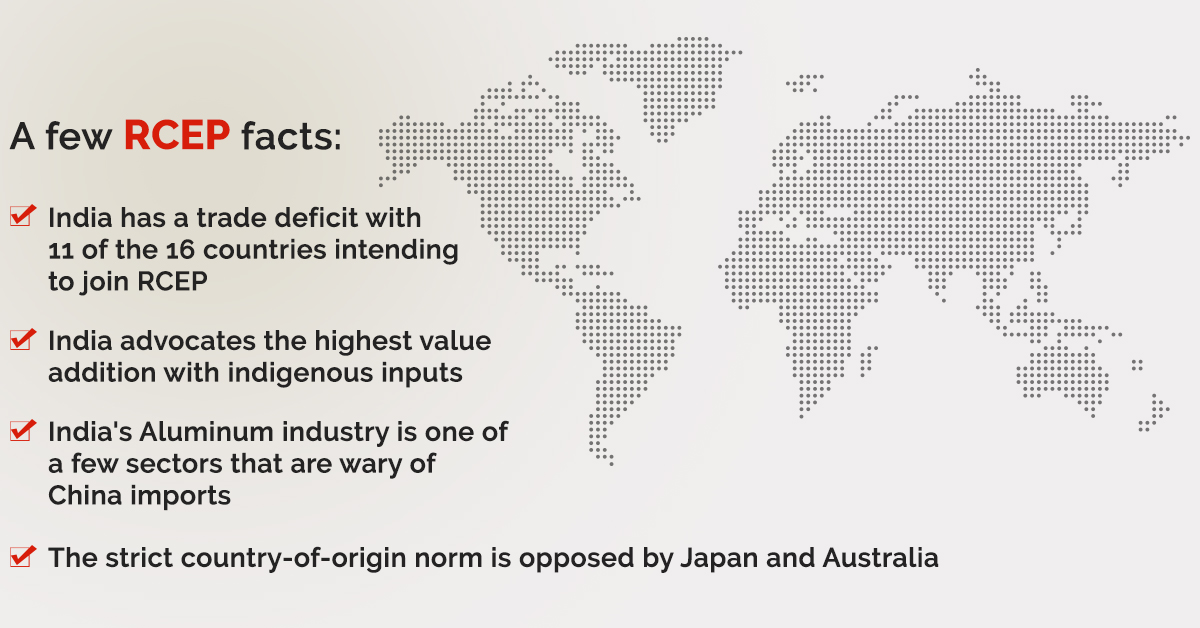

- For India, an expanded platform offers a chance to initiate better economic and diplomatic ties with the ASEAN, which have suffered after New Delhi’s withdrawal from Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

- This is an alternative for the pursuance of India’s Act East Policy.

- For Japan, which initiated the whole process of SCRI, it is evident that India, because of the border tensions with China, would be ready for a dialogue on alternative supply chains.

- In the absence of such border tensions with China, New Delhi would have done little to openly antagonise Beijing.

- The escalated India-China tensions provide the opportunity for Japan to include India in its strategic initiatives.

- This initiative would likely mean an increase in inward investment into India for manufacturing purposes.

- Thus, the initiative has taken advantage of the border tensions and COVID-19 crisis to bring together the like-minded countries to ensure a resilient supply chain that strengthens the overall regional economy.

What does the SCRI mean for Australia-Japan-India ties?

- The Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) is mainly an idea that surfaced on the contours of bilateral contracts.

- The India-Japan Special Strategic and Global Partnership is currently helping both countries (India and Japan) to enable the development of new technologies and solutions.

- They are jointly undertaking major connectivity infrastructure projects in India and subregional pockets of the Indian Ocean.

- Economic relations are also being enhanced through the “Platform for Japan-India Business Cooperation in the Asia-Africa Region” and the “Industrial Competitiveness Partnership”.

- Therefore, the India-Japan collaborations have served as a model for the sectoral cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, with the scope of including other like-minded partners like Australia.

- India and Australia recommitted to enhance their “comprehensive strategic partnership” post-pandemic by boosting collaboration in science, technology and research and strengthening and diversifying supply chain networks.

- Moreover, the two countries also committed to collaborating in the field of innovation and entrepreneurship through the Australia-India Business Exchange Programme.

- Also, Japan and Australia, which share a “special strategic partnership”, are deliberating on ways to ensure cooperation at the multilateral level for an open, inclusive and prosperous Indo-Pacific.

- The SCRI is aiming to provide new momentum to Australia-India-Japan trilateral relationship by furnishing a new foundation for collaboration within their existing frameworks.

- The SCRI’s economic focus is such that it will likely attract other countries in the region, resulting in the nurturing the three countries’ ties with the Indo-Pacific region at large, which is mutually beneficial to all those involved in the alliance.

- The idea of SCRI is, in itself, a testament to the strategic resilience of the trilateral ties.

What are the challenges?

Reluctance:

- Japan and India have clear economic motivations and distinctive strategic concerns arising from border tensions with China in East Ladakh and the Senkaku Islands.

- However, though Australia may wish to reduce its dependence on China, it will not want to jeopardise crucial links with China, the region’s largest market.

- Decoupling from the Chinese economy would be challenging for Australia and Japan.

- Compared to India’s low-level economic engagement and relatively low trade volume with China, Australia and Japan have a significant portion of trade depending on it.

- The bilateral trade between China and Australia is worth $184 billion and Japan’s bilateral trade is $304 billion.

- Besides, ASEAN nations’ participation seems unlikely given their history to being reluctant decouplers.

Unequal distribution of economic growth:

- It is impossible to designate and foster prospective areas of economic activities like semiconductors, aerospace, medical devices, textiles, chemicals and rare earth without falling into the trap of one country gaining more advantage than others do.

Unviable:

- Some firms like Toshiba and Komatsu have shifted production elsewhere in response to the US’ penalty tariffs against China.

- However, this has been at a great monetary cost.

- These companies also lost advantages that China offered with its vast domestic market and workforce, deep supplier network and reliable infrastructure.

- Therefore, while some adjustments will be made to supply chain structures like fixing the chokepoints in medical supplies, a major shift in global trade patterns is unrealistic.

- There is also the question regarding the implementation of the RCEP and RSCI by countries that are members are both these initiatives.

- Also, such rules coming on top of numerous FTAs in the region might burden the regional trade landscape even more.

India’s unpreparedness:

- Despite its size, India lacks necessary policies to provide alternatives to China within certain supply chains.

- The Make in India and other similar government initiatives have failed to provide the intended results.

- It consistently fails to make use of its comparative advantage in manufacturing.

- Though New Delhi has made the necessary efforts and attempts to promote industrialisation, there are the manufacturing bottlenecks that are unlikely to be addressed in a short period.

- Furthermore, with it being the second-worst affected country by the COVID-19, the economy is currently taking its worst hit for decades.

- It might certainly become difficult for India, which lacked the necessary requirement for establishing an industrial chain before the outbreak of the COVID-19 to do so during the post-pandemic times.

- Any international supply chain cooperation requires an open trade environment, which is exactly what India is not suited for due to its reluctance to open up its market.

- This is the reason behind India’s absence in The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP-11) and the RCEP.

- The Indian government’s current initiatives under Atmanirbhar Bharat are focused on supporting domestic industries rather than increasing foreign participation.

- This creates trust issues among foreign investors.

How does the RSCI impact RCEP?

- The proposed Resilient Supply Chain Initiative has the potential to affect regional trade agreements, including the upcoming free trade arrangement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

- India has decided to quit the grouping on November 2019 citing adverse effects on “farmers, MSMEs and dairy sector”.

- This decision, however, has not stalled its progress.

- The 10-member ASEAN group of economies from South East Asia, along with Australia, Japan, China, New Zealand and South Korea are working on its adoption in the 4th RCEP Summit which is to be held on November 2020.

- India is unlikely to revisit the prospects of re-joining the RCEP.

- However, it has decided to work with Japan and Australia on the RSCI.

- If the RSCI is expanded as intended, all Southeast Asian members will be included.

- This means that almost all of RCEP members will be a part of RSCI.

- Getting some of them to figure in the RSCI, for delinking parts regional supply chains out of China, would mean that these countries are signalling their intention to be part of the alliance to counter the Chinese hegemony.

- The challenges for RCEP would be exacerbated if Southeast Asian nations, either individually or in small groups, tend to take sides based on strategic loyalties to China or the Indo-Pacific.

- ASEAN bloc would find it difficult to handle the increasing rivalries between China and the non-ASEAN members.

- Given Japan and Australia’s complicated ties with China, the RCEP might as well be in a situation where there is little to no progress, leading to an increase in the attractiveness of RSCI.

- Japan’s decision to offer subsidies to its industries on relocating out of China has resulted in several businesses moving out to Indonesia, Laos and Vietnam.

- Other firms are also expanding their businesses or relocating to Southeast Asia.

- Thus, the investment prospects for Southeast from RSCI are considerably attractive.

- Furthermore, the negotiations for the RCEP agreement began nearly a decade ago, when the geopolitical characteristics were drastically different in the region and the rest of the world.

- In contrast, the RSCI is in line with the emerging geopolitics post pandemic.

- Therefore, there is a possibility that the RCEP would encounter unexpected problems from the RSCI.

What can be done to promote resilient global supply chain?

India:

- One of the main arguments against the success of the SCRI is India’s lack of readiness and capability to form a critical link in the alternative networks.

- India has unquestionably been slow in adopting economic reforms compared to China despite New Delhi’s push to follow Beijing’s model and attract manufacturing to the country.

- It continues to face challenges in terms of ease of doing business because of bureaucratic red-tapism, corruption and documentary compliance.

- Efficient government policies to address these issues apart from ensuring skill development are a need of the hour.

- In short term, India can use Atmanirbhar Bharat along with stimulus proposals and stable regulations to challenge China in telecom and technology, auto, cellular, textiles and pharmaceutical industries.

- Infrastructure development and bottleneck removal in land acquisition, domestic laws and liquidity can be also be ensured.

Global:

- As the changes in the global supply chains can have long-term impacts, it is vital to not be motivated by short-term considerations.

- The global consensus can be ensured to do away with protectionist and populist rhetoric advocating for onshoring of industries, which is amplified by pandemic-induced supply chain shock

- It is found that though the protectionist policies are capable of addressing short-term needs and are politically appealing, they pose considerable concerns:

- Onshoring is unfeasible technologically and economically.

- Burden for consumers as they bear the end cost of onshoring

- Hinder innovation due to reduced profits and sales and increased government interference.

- Therefore, risk reduction must be ensured by sourcing, producing and shipping of goods and services across a range of economies based on win-win agreements.

- This will limit the chances of a single manufacturing hub or shipping route creating a supply shock due to an unexpected crisis like that of the pandemic.

- Furthermore, it also prevents a few countries functioning as a cartelised oligarchy, especially in the context of specific strategically important industries like that of medical gear production, pharmaceuticals and semiconductors.

- No country in the Indo-Pacific provides viable alternatives to the business environment offered by China.

- To offset this and enable a sustainable pathway for industries to diversify their supply chains outside China, donor countries and the new host countries should collaborate to realign their development priorities with the intention of:

- Building market capacities

- Improving macroeconomic fundamentals

- Strengthening the rule of law to simplify legal codes on land acquisition, labour rights and relations

- Ensuring intellectual property rights and viable tax codes and insurance and bankruptcy policies

- Expanding judicial capacity

- To enhance the capacity building exercises, countries must scale up their infrastructure development initiatives with investments focused on transportation networks and also on digital and electronic systems that will ensure the growth of information and communication technologies.

- Developmental finance tools can be utilised to mobilise sustainable private capital investments, which can finance the multi-trillion dollar infrastructure gap in the Indo-Pacific region.

- Grants and loans can be provided to make targeted investments for trade facilitation in developing countries that are struggling to become alternative to China in a de-risked global supply chain system.

MSMEs:

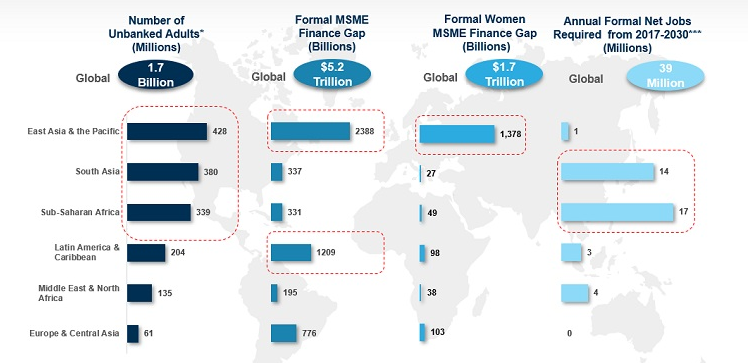

- MSMEs account for around 90% of businesses and more than 50% of employment

- Formal MSMEs contribute to 40% of the GDP in emerging economies and this number is higher when informal MSMEs are included.

- Thus, it is evident that the sector is critical for the global economic revival.

- MSMEs across numerous countries faced supply chain disruption and were at the risk of permanent closure amid the “Great Lockdown”.

- The sector is currently facing the issues of stunted operations, economic recession, unemployment, reduced income and market demand. These are threatening their survival.

- While reopening their businesses, MSMEs need a reliable, sustainable well-functioning supply chains and factors of production.

- Before the pandemic, the MSME sector already faced a USD 5 trillion financing gap.

- Now the sector is facing significant liquidity challenges and does not have the cash to diversify its supply chain.

- Development Finance Institutions and multilateral development banks can address the aforementioned issues.

- These institutions can provide financial support to the MSME sector to diversify supply chains by:

- Offering MSMEs concessional loans and grants

- Setting up enterprise funds to make equity investments in the private sectors of developing countries

- Strategically using credit guarantee to help firms transfer their credit risks developed due to the coronavirus-led economic crisis.

- Setting up syndicated loans to reduce the exposure of financial institutions when providing MSME loans.

Conclusion:

The need for the restoration of the economic normalcy necessitates the reorientation of global supply chains and building resilience within. Though RSCI is a step in that direction, it would provide little short-term benefits. The long-term strategy must be implemented without being affected by the immediate political and economic needs through international cooperation and inclusive growth.

Practice question for mains:

Do you agree with the view that the tripartite Supply Chain Resilience Initiative could have only limited impact on China’s dominance in global trade? Give reasons in support of your arguments. (250 words)

https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/what-is-the-new-idea-on-supply-chains/article32476160.ece

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PxHV2Z8wHO8

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/19/economy/us-china-trade-war-resume-coronavirus-intl-hnk/index.html

https://idsa.in/system/files/news/rusi-scri-china_compressed.pdf