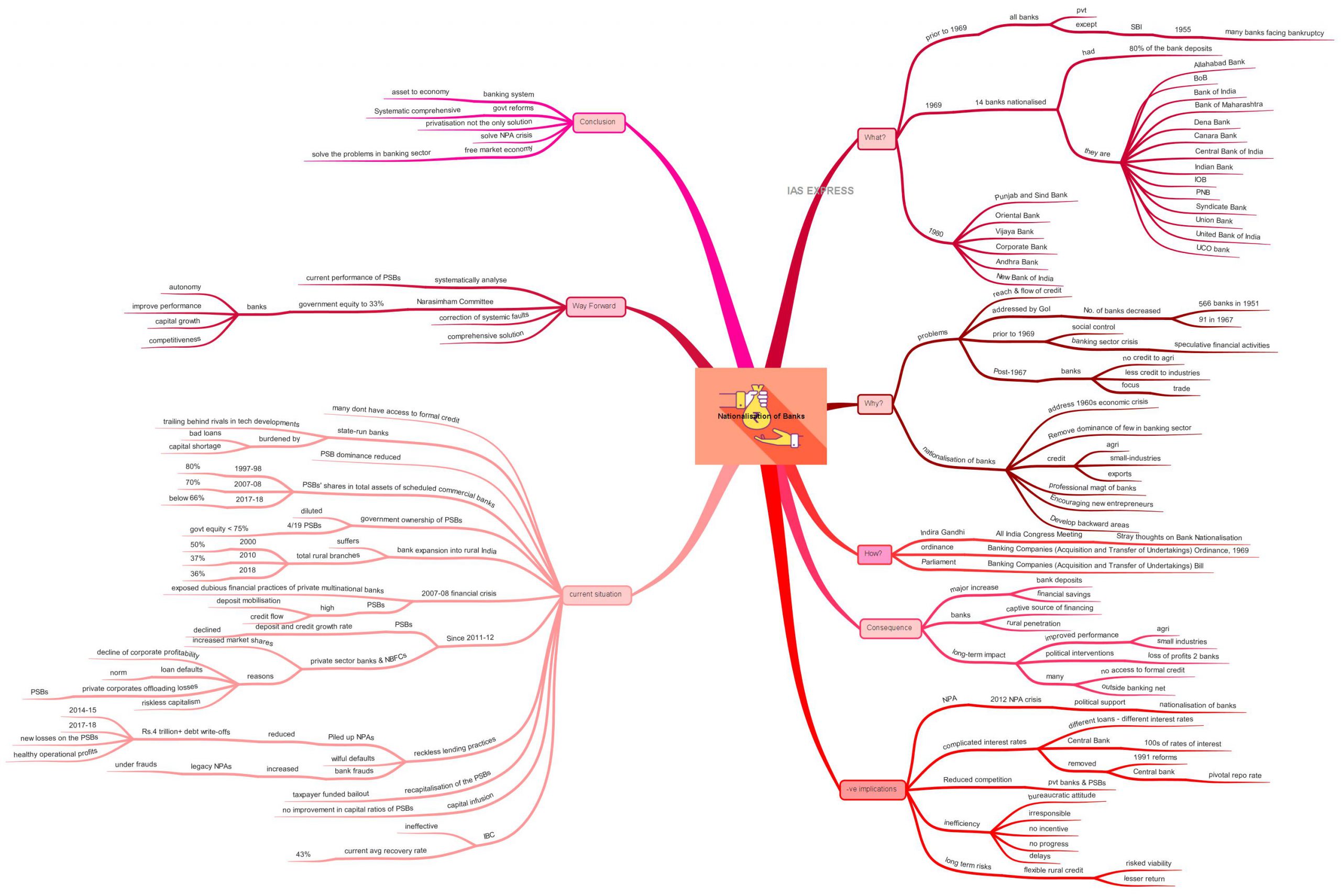

Nationalisation of Banks in India: What, Why, How, Pros & Cons

July 19 of this year marks the 50th anniversary of bank nationalisation. Nationalisation of banks is arguably the biggest structural reform introduced in the financial sector during the post-independence era of Indian history. The second volume of the official history of the Reserve Bank of India describes banks nationalisation as the single-most-important economic policy decision taken by any government after 1947. Central bank historians say in the terms of impact, even the economic reforms of 1991 pale in comparison.

What is the nationalisation of banks?

- Prior to 1969, all the banks in India, except the State Bank of India (nationalised in 1955), was owned by the private players.

- SBI was nationalised during the time when many of the private banks were facing bankruptcy at an alarming rate.

- By the 1960s, the Indian banking industry had become an important tool to enable the development of the Indian economy.

- In 1969 under the Indira Gandhi Government, 14 banks were nationalised.

- These banks, during that time, held 80% of the bank deposits in the country.

- The banks that were nationalised in 1969 are:

- Allahabad Bank

- Bank of Baroda

- Bank of India

- Bank of Maharashtra

- Central Bank of India

- Canara Bank

- Dena Bank

- Indian Bank

- Indian Overseas Bank

- Punjab National Bank

- Syndicate Bank

- Union Bank

- United Bank of India

- UCO Bank

- In 1980, the government took control of 6 other banks. They are as follows:

- Punjab and Sind Bank

- Vijaya Bank

- Oriental Bank of India

- Corporate Bank

- Andhra Bank

- New Bank of India

Why did the government nationalise the banks?

- There were numerous problems related to the reach and flow of credit to many priority sectors within the economy. Needed measures were taken by the government to address this issue. For example, the number of banks was decreased from 566 banks in 1951 to 91 in 1967.

- Before the nationalisation of banks in 1969, the government had tried to address the economic problems through “social control”.

- This was to ensure a wider spread of credit and an increase in the credit flow to emerging priority sectors.

- However, despite these measures, the banks were failing mainly due to speculative financial activities.

- Post-1967, during Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s tenure, the banks were not giving credit to agriculture and not enough credit to the industries.

- Due to this, agriculture and industries were facing a crisis during this time.

- They were more focused on extending credit for trade.

- The crisis in the banking sector had resulted in wide-ranging consequences leading to distress among the people.

- This resulted in the nationalisation of banks.

- The main objectives of nationalisation of banks are as follows:

- Address the rising economic crisis that occurred in the 1960s.

- Remove the dominance of the few in the banking sector.

- Providing sufficient credit for agriculture, small industries, and exports.

- Professionalising the management of the banking sector.

- Encouraging new entrepreneurs.

- Develop the backward areas within India

How did the government nationalise the banks?

- The then Prime Minister of India Mrs Indira Gandhi, during the annual conference of the All India Congress Meeting, had made her intentions clear on the nationalisation of banks by presenting a paper on that subject titled “Stray thoughts on Bank Nationalisation”.

- After some debates, the government issued the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Ordinance, 1969, which empowered it to nationalise banks within India.

- Within two weeks of the ordinance, the Parliament passed the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Bill, and it had received the presidential approval on 9 August 1969.

What are the consequences of this move?

- The nationalisation of banks was one of the significant events in independent India.

- This move had resulted in a major increase in bank deposits and financial savings.

- The rising fiscal deficit during that time had made banks a captive source of financing.

- The long-term impact of this move is the improved performance of the small-scale industries and agriculture.

- It has also led to increased penetration of banks into rural India.

- In the long run, the continuous political interventions had created negative effects on the profitability of the banks.

- However, the government was successful in partially meeting its goal in the developmental agenda through the banking system.

- Yet, many in India still did not have access to formal credit and a large portion of the population remained outside the banking net.

What are the negative implications of this move?

- NPA: The NPA crisis since 2012 could have, at least partly, caused due to the credit bubble that grew under the political support due to the nationalisation of banks.

- Complicated interest rates: The nationalisation of banks had led to an increasingly complex interest rate structures within the banking sector. There were different rates of interest for different types of loans. Eventually, the Indian central bank had to manage hundreds of rates of interest. Due to these complicated procedures and interests, the loans were not given to those who are need of it. This, as a result, defeated the purpose of the nationalisation of banks. This mind-boggling structure was only brought down after the 1991 reform, with the central bank managing the pivotal repo rate, while the commercial lending rates were decided by the banks themselves.

- Reduced competition within the banking sector: Banking is a highly competitive sector. However, the nationalisation of banks had reduced the competition between the public banks and private banks.

- Inefficiency: Due to the nationalisation of banks, there was a bureaucratic attitude in the banking sector. There was no responsibility, accountability or incentive for it to progress within the public sector banks. Unwarranted delays were the new norm within these banks.

- Long-term risks: Though liberal credit is necessary for the development of rural India, it had also created harmful effects on the stability of the banking sector. The nationalised banks are now facing the problems of overdue loans and the establishment of economically unviable branches. Extending loans to agriculture and small-scale industries has proven to be a risky endeavour as it had given lesser returns. These loans were a risk to the economic viability of such institutions.

What is the current situation?

- Although the government had succeeded in partially meeting its goal of implementing its developmental agenda through the banking sector, many in India did not reap the benefits intended by the nationalisation of banks.

- Many still don’t have access to formal finance.

- Several state-run banks are trailing behind their rivals in the technological developments. They have to compete with new private banks that came up 25 years later with the state-of-the-art technology.

- Although the government control has reduced since liberalisation, the banks are burdened with the majority of the bad loans and are starved of capital.

- The government has considered a reduction of equity ownership and capital infusion to strengthen the public banking system.

- With the state policies shifting towards liberalisation and privatisation in the last three decades and the entry of new private banks, the dominance of the public sector banks (PSBs) has been reduced.

- The share of PSBs in the total assets of the scheduled commercial banks, which was over 80% in 1997-98 had reduced to around 70% by 2007-08 and further to below 66% in 2017-18.

- Government ownership of the PSBs has been diluted over time, with 4 out of 19 currently operating PSBs having government equity less than 75% with that of largest PSB, the SBI, at below 58%.

- The banks’ expansion in rural India has also suffered, with the share of total rural branches falling from 50% in 2000 to 37% in 2010 and a further 36% in 2018.

- The global financial crisis in 2007-08 had exposed the dubious financial practices of the private multinational banks.

- During the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2007-08, both the deposit mobilisation and credit flow of the public sector banks in India had witnessed a phase of higher growth compared to the private sector banks.

- Since 2011-12 though, the deposit and credit growth rate of the PSBs has declined with private sector banks and NBFCs gaining market share at the cost of the PSBs.

- This is due to the fact that, with the decline of the corporate profitability after 2011-12, loan defaults became the norm with the private corporates offloading their losses onto the PSBs.

- This phenomenon was termed as “riskless capitalism” by a former governor of the RBI.

- The previous UPA government and the RBI were also responsible for encouraging reckless lending practices.

- The piling up of the NPAs, wilful defaults and bank frauds has continued under the Modi regime.

- The NPA reduction in the very recent period has happened due to the Rs.4 trillion-plus debt write-offs effected between 2014-15 and 2017-18, which have inflicted record new losses on the PSBs, despite posting healthy operational profits.

- The bank frauds have also shot up with many legacy NPAs now being classified as frauds.

- In this context, the successive doses of capital infusion by the government have not been able to improve the capital ratios of the PSBs significantly.

- The recapitalisation of the PSBs under the present dispensation has been more of a taxpayer-funded bailout of the loan delinquent corporates and fraudsters.

- The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code process has so far not been effective in yielding the timely NPA recovery.

- The average recovery rate is currently 43%, which implies a 57% loss for the banks.

- Unless this improves significantly, and tough punitive action against the bank frauds and wilful defaulters are initiated transparently, PSB loss will continue to mount.

- The merger of PSBs and the disinvestments have proven to be inefficient and may further weaken the PSBs.

- Hence the PSBs require a major course-correction.

What can be the way forward?

- It is evident that the nationalisation of banks has provided both the negative and positive impacts in the Indian banking sector and economy.

- The 50th anniversary of the nationalisation of banks can be a good occasion to systematically analyse the current performance of the PSBs and the necessary steps can be taken to improve the banking sector.

- There are some obvious negative consequences that should be looked into for the future growth of India’s banking system.

- Thus, it may be prudent now to look into the recommendations of the Narasimham Committee on the banking sector reforms.

- Bringing down the government equity to 33% will give the banks the much-needed autonomy to improve their performance and growth.

- It will also improve banks’ capital growth and competitiveness in the market.

- It would prove to be more practical if the systemic faults are corrected instead of focusing on only the financial inclusion.

- Even a merger may prove to be counterproductive in this situation if the existing faults are not taken into account.

Conclusion

The banking system has proven to be of significant asset to India’s economic growth and development. In recent times, there is an increased call for privatisation of the banks to solve the current problems faced by the banking sector. The privatisation of banks is not a panacea. Systematic comprehensive governmental reforms must be initiated to resolve the NPA crisis and creation of free-market to revive the investments into the economy. This, if done correctly, would ensure the economic prosperity of the country.

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.