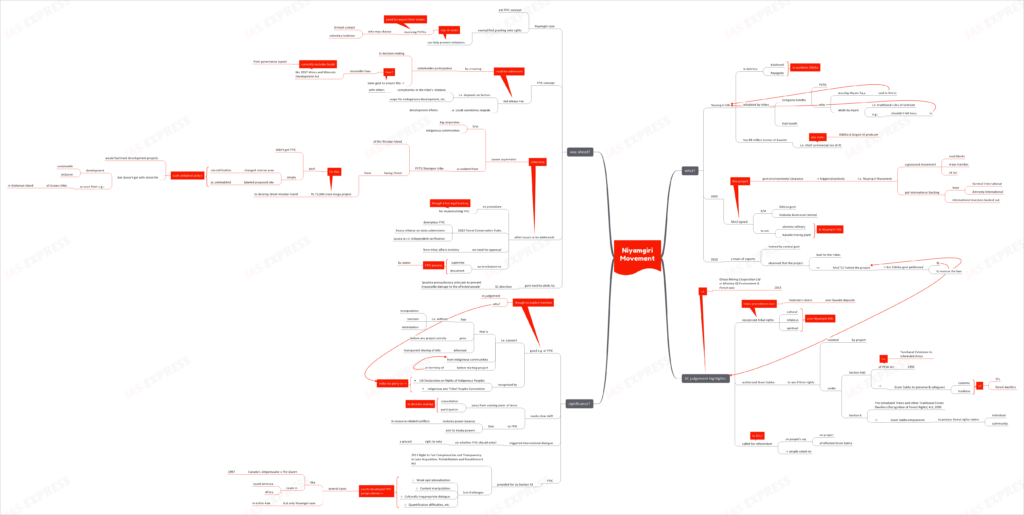

Niyamgiri Movement- Importance of the FPIC Concept

2023 marks 10 years since the historic Niyamgiri Referendum in which the tribal people of southern Odisha gave a resounding no to a bauxite mining project in the Niyamgiri Hills. The Niyamgiri Movement, continues to hold relevance for tribal rights in India, even today.

What is the Niyamgiri Movement?

- Niyamgiri is a hilly region in the districts of Kalahandi and Rayagada in southern Odisha.

- It is peopled by the Dongoria Kondhs- a PVTG (Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group) and the Kutia Kondh.

- These tribal communities consider the hills to be the abode of their God, Niyam Raja.

- They abide by the ‘niyam’ i.e. traditional rules of restraint with regards to use of natural resources. For instance, felling trees in the Niyamgiri hills is forbidden among the tribes.

- However, the hills have some 88 million tonnes of bauxite reserves. Note that bauxite is the chief commercial ore of aluminium and Odisha is the largest producer of aluminium in India.

- In 2003, the state government signed an MoU with Vedanta Aluminum Limited to set up an alumina refinery and a bauxite mining plant in the Niyamgiri hills.

- In response to this, the Niyamgiri Movement started as a grass-root people’s movement against the environment clearance given to this mining project.

- The tribal members blocked roads leading to the hills and conducted mass marches and sit-ins in Bhubaneswar.

- Over time, the movement received backing from international organizations like Amnesty International and Survival International. The international attention resulted in several international investors selling their stocks in the company.

- The government constituted a team of experts in 2010. This team concluded that the mining project would have a detrimental effect on the tribes. Following this, the Union Environment Ministry put the project on halt.

- However, the state government (through the Orissa Mining Corporation Ltd.) petitioned the top court to reverse the ban on mining.

Highlights of SC Judgement:

In 2013, the Supreme Court gave its judgement, in favour of the tribes, in the historic Orissa Mining Corporation Ltd vs Ministry Of Environment & Forest case:

- The court recognized the tribes’ cultural, religious and spiritual rights over the Niyamgiri hills as taking precedence over Vedanta’s claims over the bauxite deposits.

- It authorized the Gram Sabha to examine whether their rights were violated by the proposed project, under

- Section 4(d) of PESA (Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996. Under this section, the Gram Sabha is to safeguard and preserve the customs and traditions of the Scheduled Tribes and other forest dwellers.

- Section 6 of The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 that empowers the Gram Sabha to process individual and community forest rights claims.

- The court also ordered a referendum asking for consent for the proposed project. The people of the affected Gram Sabha voted in it. The result- a resounding no.

Why is this significant?

- The Niyamgiri case is considered as a good example of the use of FPIC or free, prior and informed consent from indigenous communities before commencing a project in their territory.

- In FPIC:

- Free- absence of manipulation, coercion and intimidation when getting consent

- Prior- consent sought before any project activity is started

- Informed- transparent sharing of all necessary and material information

- FPIC is recognized by:

- UN Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention

- In FPIC:

- Note that the judgement has no explicit mention of FPIC norm or other international human rights. This is because India isn’t a signatory to either of the 2 conventions.

- However, this marks a clear shift away from the previously existing norm of mere ‘consultation’ or ‘participation’ in decision making. The FPIC approach has been pivotal in restoring the power balance in such resource-related conflict resolutions. It is almost akin to giving treaty making powers to indigenous communities.

- The Niyamgiri case triggered international dialogue on whether FPIC rights should entail a right to absolutely veto a project.

- While FPIC norm is provided for by Section 41 of the 2013 Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, the actual usage of this norm is plagued by:

- Weak operationalization

- Content manipulation

- Culturally inappropriate dialogue

- Quantification difficulties, etc.

- This has left the courts to develop FPIC jurisprudence and to ensure its effective implementation. While there have been several cases on FPIC like Canada’s Delgamuukw v The Queen in 1997 and cases in South America and Africa, the Niyamgiri case remains the sole example from the entire Asian region.

What is the way ahead?

- The Niyamgiri case established the concept of FPIC in India.

- It exemplified that granting veto rights can help prevent violations, especially in cases involving PVTGs who choose limited contact or even voluntary isolation. It is vital to respect the wishes of such vulnerable groups.

- However, the outcome of FPIC is not always positive i.e. it depends on factors like complexities in the tribe’s relations with others, scope for endogenous development, etc. Sometimes, this could impede the state government’s efforts towards the community’s development.

- This could be addressed by ensuring that the communities are roped-in as significant stakeholders in the decision making process. This onus of ensuring inclusivity falls on the state governments.

- Towards this end, the government could reconsider laws like the 1957 Mines and Minerals Development Act which currently exclude local communities from the governance aspect.

- The fact that there is still no procedure in place for implementing the FPIC provisions, despite its legal backing, is a matter of concern. In fact, the 2022 Forest Conservation Rules downplays the need for FPICs. Instead, excessive reliance is placed on the state governments’ submissions while leaving a lacuna with regards to independent verification of project proposal.

- Another shortcoming in the procedure for verifying project proposals with implications for indigenous communities is that there is no requirement for approvals from the Tribal Affairs Ministry.

- There is also the need to have a mechanism in place to supervise and document the FPIC process undertaken by the state.

- Without addressing these deficiencies, the power asymmetry between the big corporates and the indigenous community will continue to be a sad reality.

- For eg, the PVTG Shompen tribe of the Nicobar Island face a threat from the Rs 72,000 crore mega project to develop the Great Nicobar Island.

- The government simply changed the reserve area using a notification and notified the proposed project site as ‘uninhabited’, without seeking any FPIC from the tribes.

- While such unilateral interventions would fast track various development projects, it could lead to unabated exploitation of natural resources- something that doesn’t gel with our vision for sustainable and inclusive development. This is evident from the situation faced by the Jarawa tribe on the Andaman Island.

- Hence, the government needs to abide by the top court’s direction in the OMC v. MoEF i.e. ‘practice precautionary principle to prevent irreparable damage to the affected people’.

Conclusion:

The Niyamgiri judgement, incorporating the concept of FPIC, was the product of extraordinary efforts of legal mobilization, at the grassroot level, against the disproportionately more powerful corporate forces. However, it remains an exception to the trend of tribal interests being sidelined in pursuit of ‘development’. There is a need to address this power asymmetry.

Practice Question for Mains:

2023 marks 10 years since the historic Niyamgiri Referendum. What significance does this movement hold for the current situation in India? How should we proceed with regards to development goals? (250 words)

If you like this post, please share your feedback in the comments section below so that we will upload more posts like this.